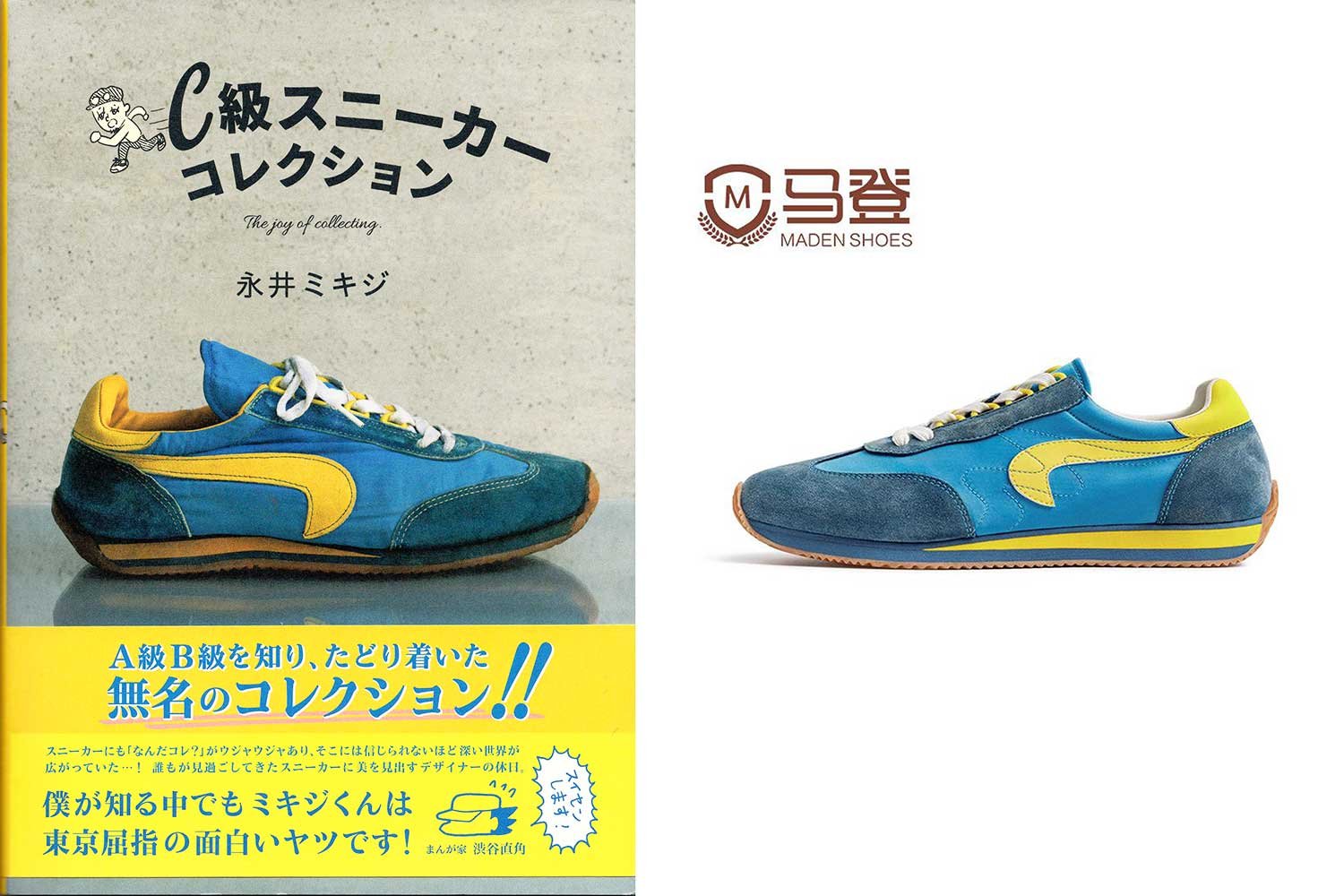

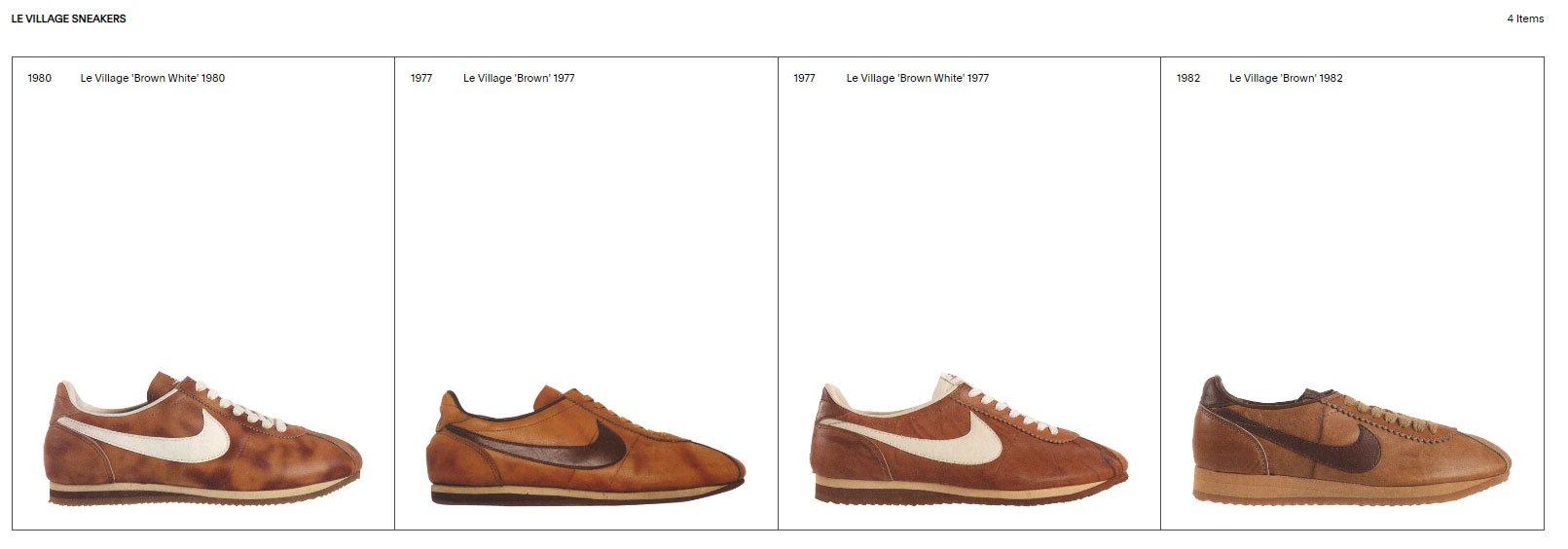

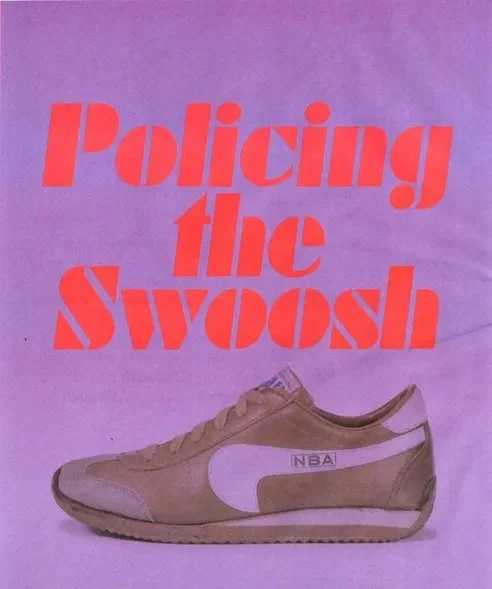

Outsourced private labeling in practice

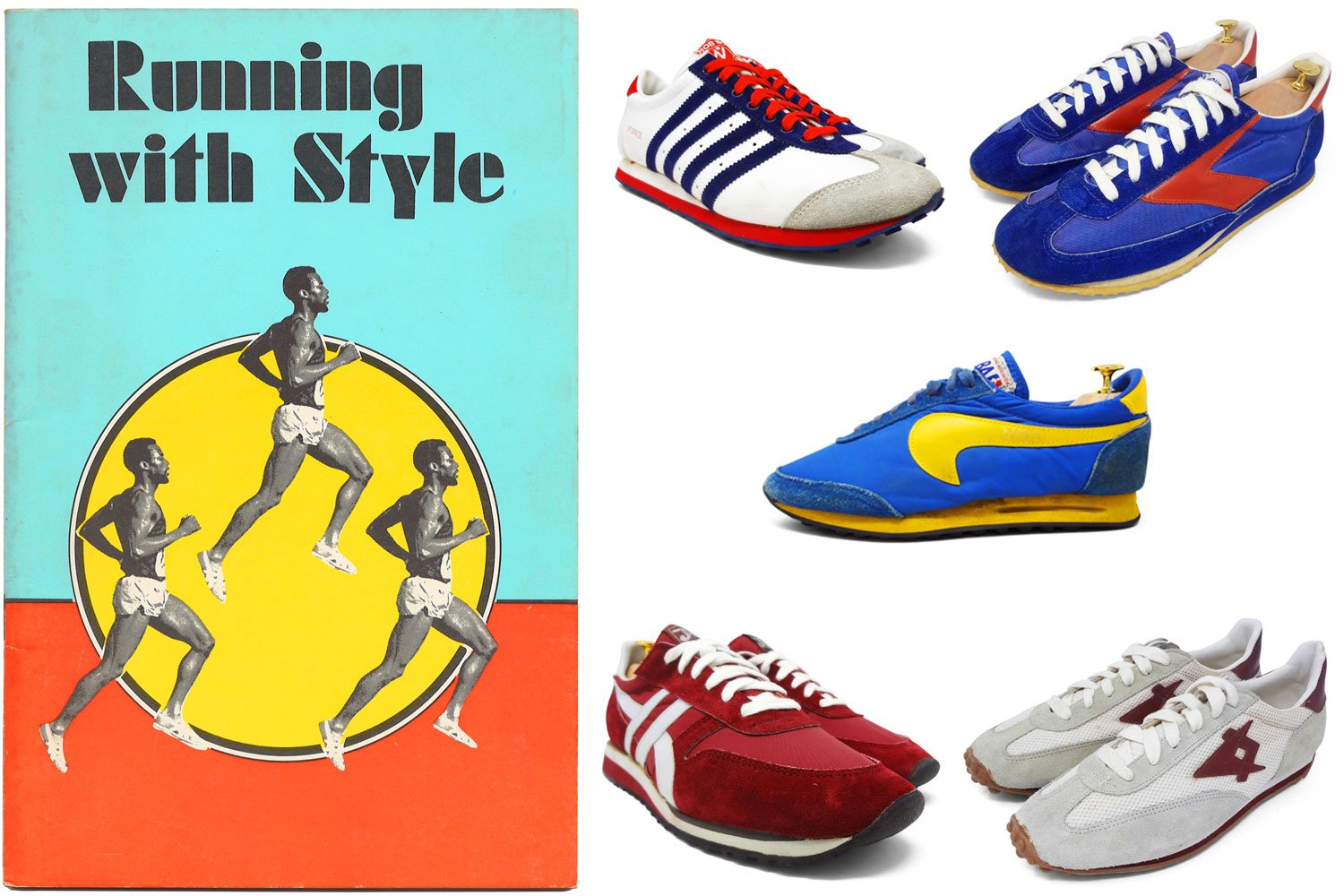

Why would sporting goods and large department stores like Sears outsource their sports shoe manufacturing to other brands? In a word… expertise. Sears, JC Penney, Nordstrom and others may not have had the inhouse skills required to set up their own sneaker line so instead they outsourced it to brands like adidas and Converse that were already successful in footwear. These department stores wanted to give their customers similar styles sneakers at a lower cost and it makes sense that they would not want to spend the time or money to design their own shoes and set up an entire manufacturing supply chain. With the private label setup they just had to come up with their own brand name, make minor changes to a product that already existed and then slap some branded labels on it. It was easier to outsource it.

It might seem counterintuitive to create a brand for other companies but from the sneaker manufacturer’s side of this deal they also must have benefited from this arrangement as well. Some of the ways that we can think of this being beneficial for them are the following:

A larger footprint for consumer reach - having products stocked in a department store like Sears gave them national distribution within the Sears network without having to open their own stores across the country.

Premium shelf space within the department store.

Valuable shelf space taken away from their competitors in America’s largest retailers.

Another revenue stream.

On the factory manufacturing side there were also probably benefits including:

Reaching factory order minimums

Testing out new factories capabilities without using their own branded product

Testing possible new designs under another brand name

A big part of this arrangement is that it was usually not brand damaging because in some cases it was hidden from the consumer. Also department stores were not seen as competitors to sporting good brands like Nike and adidas but instead seen as allies. Sears and Nordstrom’s customers would probably be shopping for leisure footwear while Nike and adidas were trying to dominate in the arena of competitive athletic footwear. For a long time we've wondered that if this was such a common practice then was Nike involved in it too? It turns out that they were. The quote below is from the book Swoosh by J.B. Strasser and Laurie Becklund:

“(Jeff) Johnson's duties read like a list of everything Knight wished for and couldn't afford: R&D, inventory control, advertising, promotions, exports, private label sales to other wholesalers, and company newsletters.”

Jeff Johnson was Nike’s first employee. Private label sales to other wholesalers?

Interesting.

CHECK YOUR SOURCES

Who is J.B. Strasser and Laurie Becklund?

The articles over the next few days are based on the description above from the book Swoosh by J.B. Strasser and Laurie Becklund and Nike co-founder Phil Knight’s book ‘Shoe Dog’ so it’s probably important to understand who the authors are and what their relationship to Nike was.

J.B. Strasser, now Julie Dixon, was a Nike’s first advertising manager. If the name Strasser looks familiar it is because she was married to Rob Strasser, the man who was a pivotal early leader in Nike’s history and brought Michael Jordan into the fold at Nike. Laurie Becklund was J.B. Strasser’s sister and an award-winning former staff writer at the Los Angeles Times.

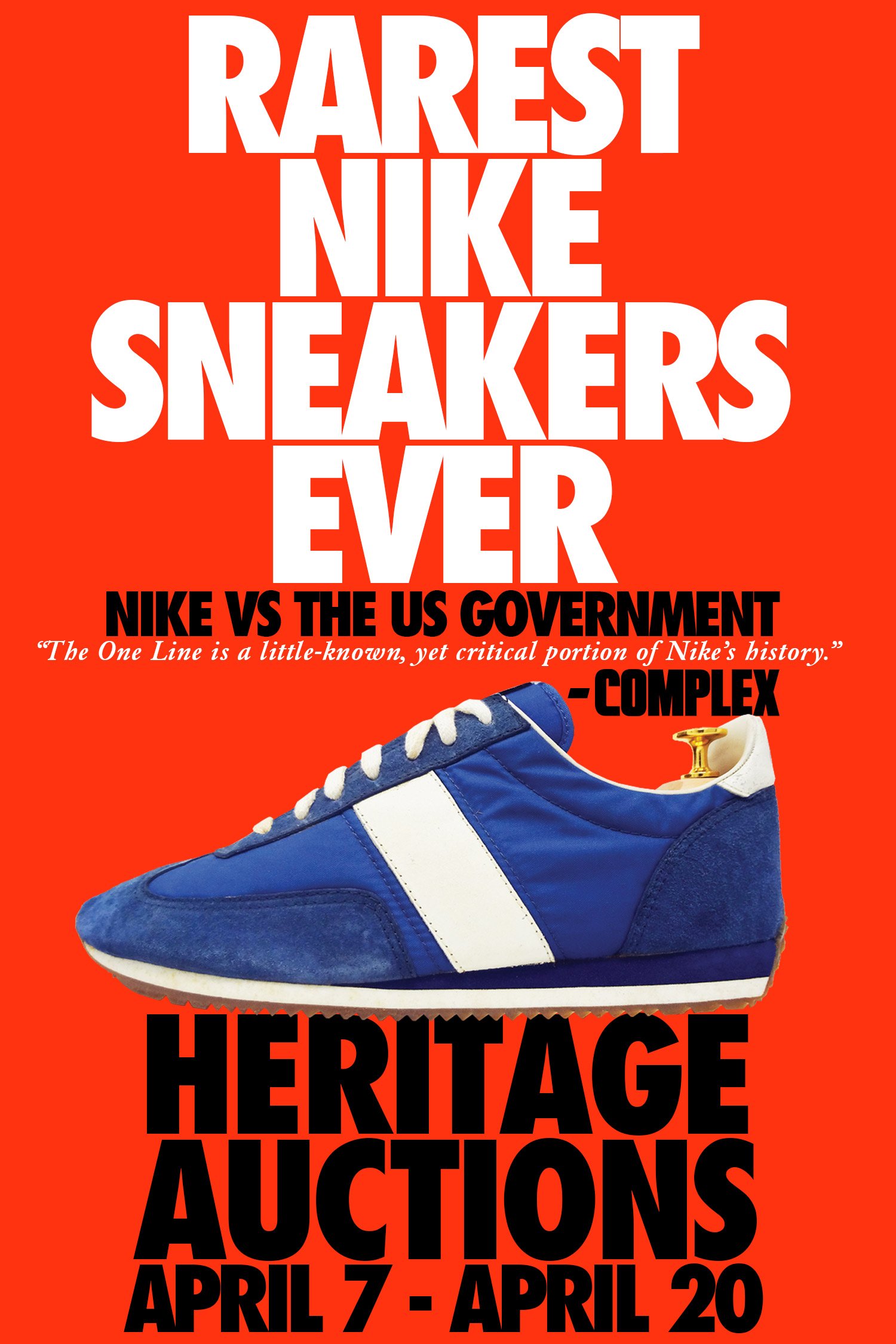

‘Swoosh: Unauthorized Story of Nike and the Men Who Played There’ is an insider account of early Nike and was verified by multiple sources and early Nike employees. The contents of the book hit so close to home that Nike co-founder Phil Knight threatened to sue J.B. Strasser. From the Seatle Times:

Author Julie Strasser was the Beaverton, Ore.-based company's first advertising manager. Her husband, Rob Strasser, was part of the core management team and a close friend of Nike founder Philip "Buck" Knight. Rob Strasser, who had been associated with the company since the early 1970s, resigned in 1987. Laurie Becklund, co-author, is Strasser's sister and a Los Angeles Times reporter.

Despite Strasser's connections, or perhaps because of them, Knight never agreed to cooperate with her on the book. In fact, he opposed the project and threatened to sue, Strasser says.

Together Strasser and Becklund plowed through 30 years of Nike files and lawsuits, and interviewed most people associated with the company. Despite the lack of written documentation from the early years, Strasser insists "Swoosh" is accurate. In most cases, she says, two or three different sources corroborated information about particular scenes described in the book.

For those of you who have not read Swoosh yet I highly recommend this book if you want to learn about early Nike history. The book was reviewed in the New York Times as 'Chariots of Fire' meets 'Animal House.' It’s a great book and a bummer that it never made it to Kindle.

WHICH BRANDS WERE PRIVATE LABELED NIKE MANUFACTURED SHOES?

Sifting through the possibilities

One way to start to figure out which brands Nike made private labeled sneakers for seemed to be to look at the brands that Phil Knight worked closely with in his book Shoe Dog on the Nike ‘Futures’ program. The assumption here is that he’d want to keep these kinds of deals with brands that he had pre-existing business relationships with and trusted. From Shoe Dog:

“I had an idea. Why not go to all of our biggest retailers and tell them that if they’d sign ironclad commitments, if they’d give us large and nonrefundable orders, six months in advance, we’d give them hefty discounts, up to 7 percent?

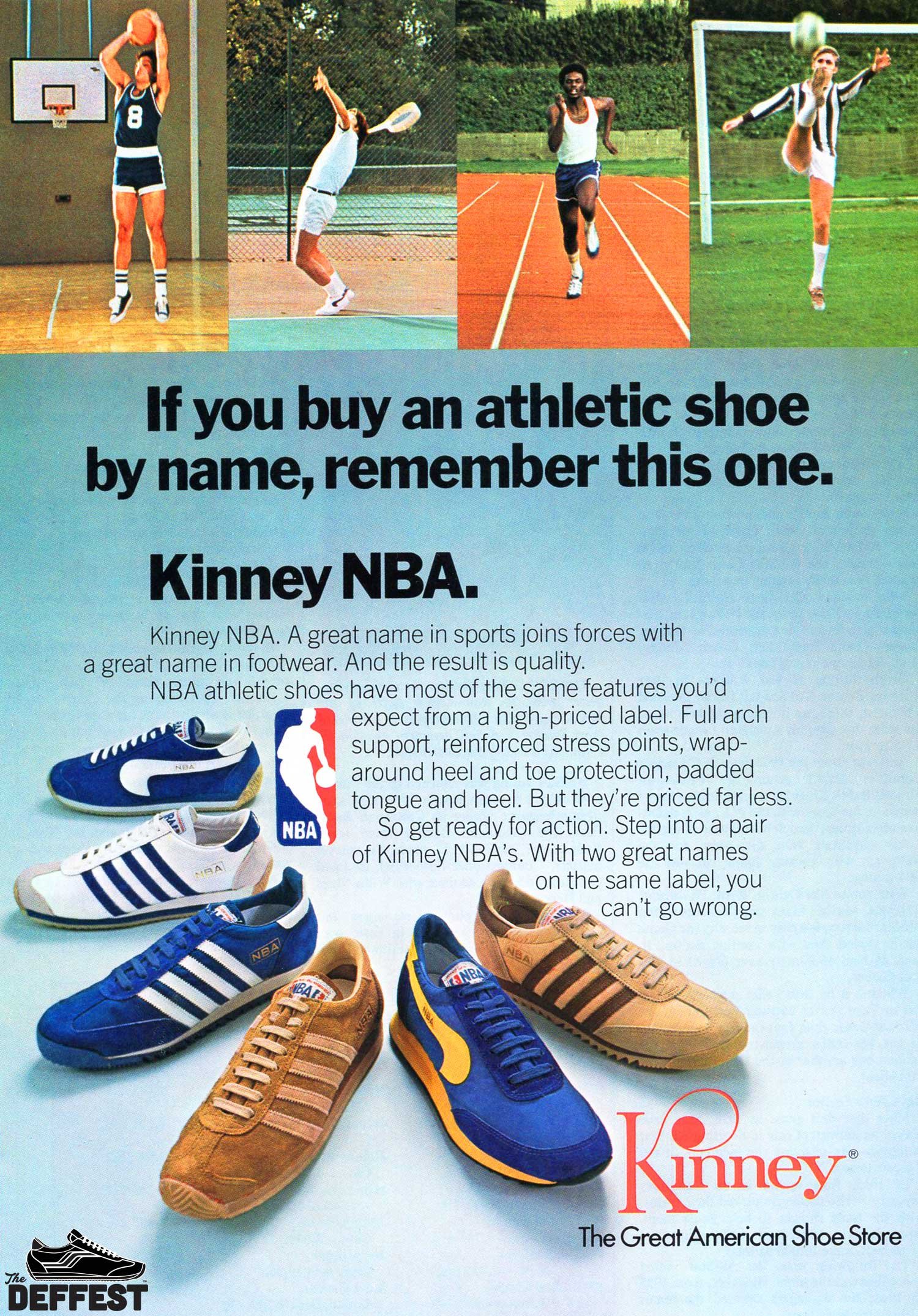

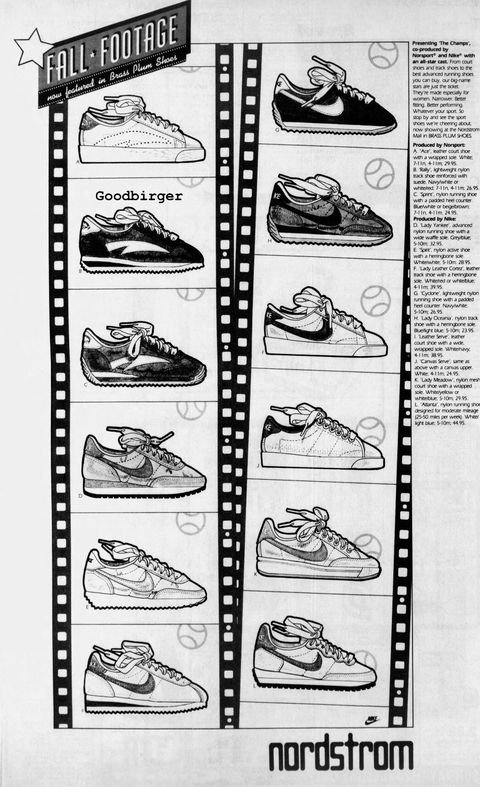

This way we’d have longer lead times, and fewer shipments, and more certainty, and therefore a better chance of keeping cash balances in the bank. Also, we could use these long-term commitments from heavyweights like Nordstrom, Kinney, Athlete’s Foot, United Sporting Goods, and others, to squeeze more credit out of Nissho and the Bank of California… I told them that this program, which we were calling “Futures.””

This seems like a decent starting point.

WHAT WAS NIKE’S RELATIONSHIP TO NORDSTROM?

Nordstrom seems to have been the main department store that stocked Nike products in the 1970s and 80s. Sears was a bigger department store than Nordstrom at that time but did not stock Nike sneakers in their U.S. catalogs between the mid 1970s and 80s. Both brands had in common that they hailed from the Pacific Northwest, with Nike based in Beaverton, OR and Nordstrom located in Seattle, WA. Here’s more on Nike’s relationship with Nordstrom from Swoosh:

Moodhe mentioned his idea to Knight and Hayes, and a program was developed called "Futures." The idea behind Futures was to offer major customers like Nordstrom an opportunity to place large orders six months in advance, and have them commit to that noncancellable order in writing. In exchange, customers would get a 5 to 7 percent discount and guaranteed delivery on 90 percent of their order within a two-week window of time. If retailers went for it, Blue Ribbon had a unique forecasting tool.

Also, since the shoes were presold, the retailer, not Blue Ribbon, took the risk. That brought up a good point: A big department store chain like Nordstrom had a better credit rating than Blue Ribbon. Shouldn't an order from a blue-chip company count as an asset?

Nordstrom and Nike were close enough to co-sponsor the annual ‘Beat the Bridge’ running event starting in 1982. In the early years of this event Nordstrom silk screened the shirts onto Nike blank ringer t-shirts. It seems like there was a level of coordination happening between the two brands.